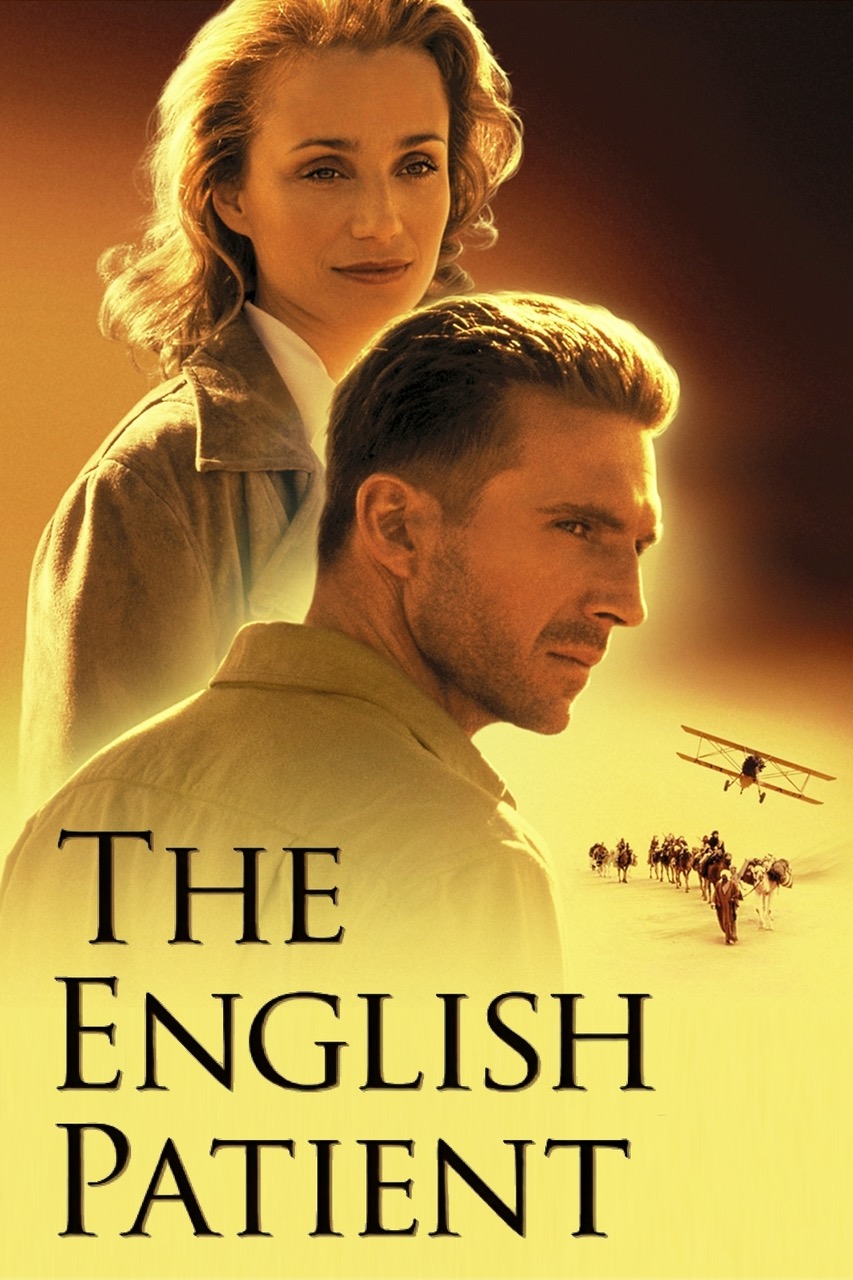

The English Patient

Please

note the purpose of this blog is to discuss established classics that

I've never seen. As such, the following is laden with spoilers.

Why So Long?

Very long and very very boring...are six words that every Irish person has forever connected in their heads to The English Patient. And it would be a lie if I didn't admit they did play at least a small role in my taking of twenty-four years in getting around to this one. The main factor though was a sense of familiarity, this was a film who's effect, at least the initial one, is dependent on you not knowing the story of the two people in the plane crash at the start. Between its haul of nine Oscars and the accompanying attention that comes with that kind of thing, and of course the parody on The Adam and Joe Show I knew full well who they were and why they were in that plane.

And?

Well it is very long, there's no escaping that but I am glad to discover its not even remotely boring. Instead, I found a David Lean-esque epic, a grand picture with huge vistas that is all about, indeed hinges entirely on, the massive effects of our small decisions. I gather there's quite a bit of the book that didn't make the screenplay (no bone to pick, generally the fashion with the better adaptations) but Minghella is due a lot of credit for taking quite the complex story, made to be told in a complex manner but delivering it with such clarity and engagement. Questions abound through acts one and two but all are answered as act three brings us to our conclusions. Tales of love, loss, betrayal and the outbreak of World War Two, all funneled through an abandoned monastery in Allied-Occupied Italy.

The recurring theme of the small decision with a huge impact, or butterfly effect, is unquestionably what I found to be most interesting in the film. There's the little obvious ones sprinkled throughout; Kip (Naveen Andrews) is a bomb disposal expert, a man who's entire job is small movements of the hand that either save many lives, or end them instantly. But key to the film is the small decision we learn of in the final act, that Almasy (Fiennes) traded his maps of the Sahara to the Nazis to get a plane. Almasy simply wants to get back to his love, to keep his promise. The Allies attempted to imprison him on account of his name, and in 1939 Almasy could have no idea of what horrors the Third Reich would inflict on the world. In that moment they were just another imperial European power with an antisemitic streak - just likes the Brits really. It is that decision that, in this story anyway, leads to the Nazis taking control of Cairo and places Almasy on a collision course with Willem Dafoe's vengeful Caravaggio.

If we take this decision and pair it with Juliette Binoche's Nurse, we get to central crux of the film. Even if we choose not to believe in the idea of a pre-destined fate, what control do we really have over the larger courses our lives travel. Binoche's Hana is a Nurse who believes herself to be cursed, as everyone who gets close to her dies. Yet this does beg the obvious question, given her profession and the raging global conflict within which she conducts her duties, how much responsibility should she really be taking for the death around her? And even though the obvious response is "pretty much none", she would not be alone in believing she has played an integral role in this suffering. Hana of course, comes to find that she is not cursed and finds love with Kip as the Armistice is declared. Almasy escapes justice, both official and personal but only because the break between his actions and their consequences are made abundantly clear.

Will You Be Watching It Again?

Definitely wouldn't turn it off if I found it playing somewhere one evening, thoroughly enjoyed this one.

Has Any Light Been Shone on Some Heretofore Unknown Bit of Pop Culture?

No, this one was simply too omnipresent to hold any surprises. That said, I did immediately go on YouTube and rewatch The Toy Patient and my admiration for Joe Cornish as a director has only increased (from a fairly lofty position it must be said). It's genuinely incredible the work the two lads put into recreating the images from the film. Also, didn't know Detective Lewis was in this nor did I know that he'd meet his fate in such an inventive manner.

Comments

Post a Comment